Suggesting Connections (Part I)

The Standard Works contain 41,995 verses and 45,985 cross-references between verses. If we ignore the directionality of these references, there are 26,946 connected verse pairs. These connections represent only a fraction of the possible number of verse pairs (26,946 / 881,769,015 = 0.003%). Of course, we know that not all verse pairs are interesting—Joshua 18:25 and D&C 10:30 really don’t have anything in common—but there are definitely interesting connections that the existing cross-references have missed.

This post explores several methods for algorithmically suggesting new connections in the scriptures. There’s no ground truth here; the validity of a connection is mostly subjective. That said, with the hope of being useful and revealing new insights, the Connection Explorer now includes suggested connections beyond the existing cross-references.

Similarity between verses

Connections between verses are fundamentally statements about their similarity. Verses can be similar in any number of ways: perhaps they refer to the same person or event, or discuss the same doctrinal principle, or contain the same idiom or phrasing (“And it came to pass…”). Depending on what we are looking for, different flavors of similarity will be more or less relevant.

Unfortunately, the existing cross-references do not have any notion of kind; different notions of similarity are mixed and matched without any warning. Resources like the Topical Guide help to organize references by the type of similarity they share; however, much of their utility is easily approximated by modern keyword searches. Ideally we could use data science and machine learning to identify non-obvious connections that go beyond existing tools.

Before I bite off more than I can chew, let’s start with some simple approaches that can be used to expand the existing set of connections (whether obvious or not).

Representations and metrics

From a data science perspective, similarity calculations require two ingredients: a representation and a metric. The most common representation is a vector, where each component holds information about some property of the object. For example, a bag-of-words representation of a document is simply the number of instances of each word from a predefined vocabulary.

Metrics are used to combine the representations for two objects and return a similarity or distance value. In text processing tasks, two of the most common metrics are cosine similarity and Euclidean distance. The metric values can be used to identify the most similar pairs, either by imposing an absolute cutoff or by considering only the top-ranked pairs.

Looking at neighbors

One of the simplest ways to measure similarity between verses is to compare their neighborhoods—the connections they have in common. In this case, the vector representation of each verse is simply its corresponding row in the adjacency matrix of the undirected graph. There is an entry in the vector for each verse in the graph, with a 1 where two verses are connected and a 0 otherwise. Conceptually, the nonzero entries in this vector define a set of neighbors; for example, the neighborhood set for Hel. 5:8 is {1 Ne. 15:36, Hel. 8:25, 3 Ne. 13:20}.

The Jaccard coefficient is a common metric for comparing binary vectors or sets. It is defined as the set intersection divided by the set union; in our case, this is the number of neighbors two verses have in common divided by the total number of neighbors for both verses (after removing duplicates). The metric equals zero when there are no neighbors in common, and one when all neighbors are shared.

Consider 2 Ne. 26:24 and 3 Ne. 9:14, which are not connected by any existing cross-references. The neighborhood sets for these verses are, respectively, {John 3:16, John 12:32, 2 Ne. 2:27, 2 Ne. 9:5, Jacob 5:41, Alma 26:37} and {Isa. 59:16, John 3:16, 1 Ne. 1:14, 2 Ne. 1:15, 2 Ne. 26:25, Jacob 6:5, Alma 5:33, Alma 5:34, Alma 19:36}. These verses have one neighbor in common (John 3:16) and 14 unique neighbors between them, so the Jaccard similarity is 1 / 14 = 0.07.

As an aside, identifying connections this way has an interesting property: it is iterable. If we add the top-ranked connections to the existing set, we can repeat the analysis to suggest another new set of connections. If we had the patience, we could repeat this procedure until the set of connections doesn’t change anymore. (For simplicity, we will not iterate in this post.)

Analysis

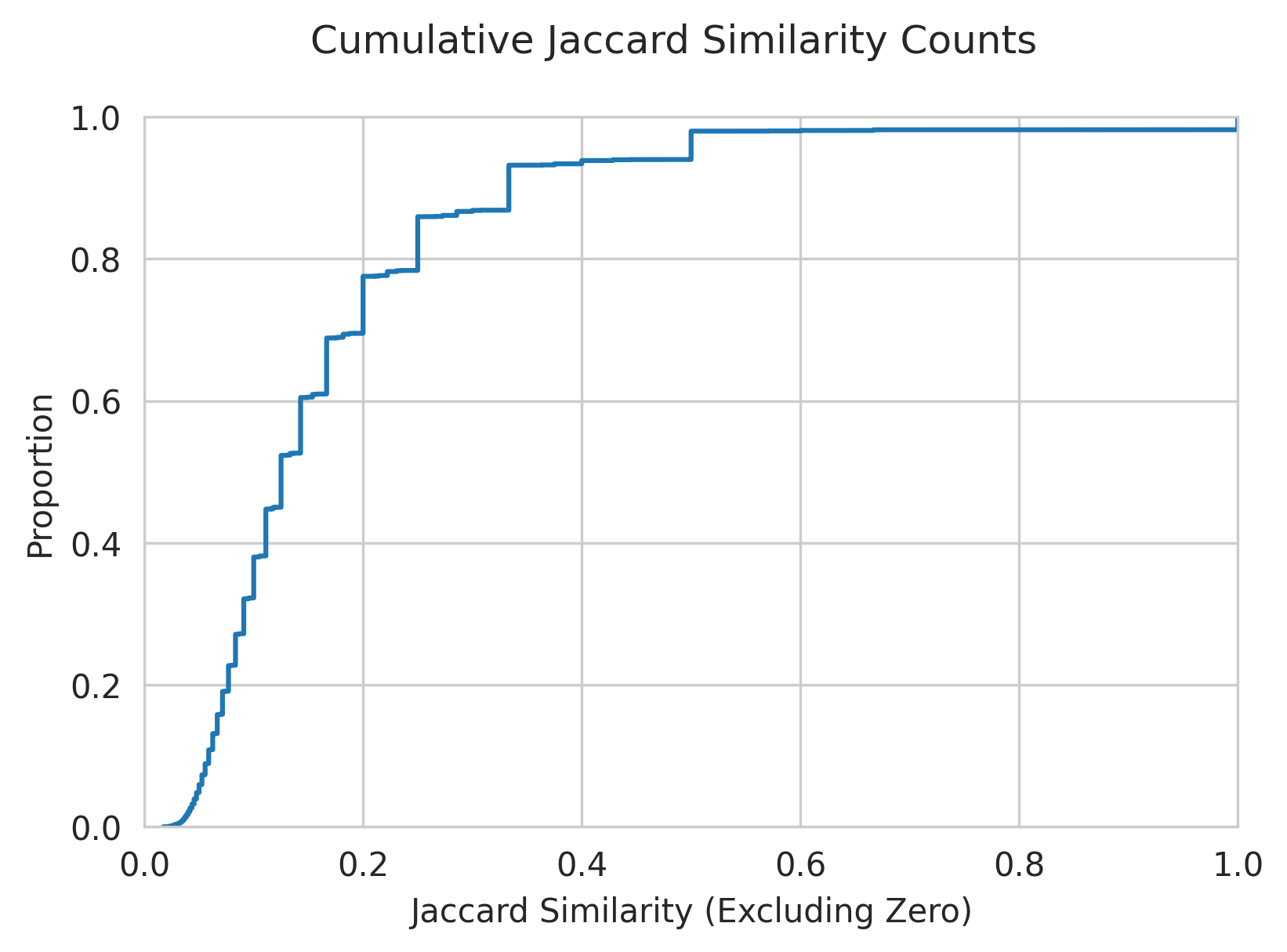

Since over half of the nodes in the graph have no incoming or outgoing references, most of the pairwise Jaccard similarity values are zero. In fact, only 95,247 verse pairs have any neighbors in common (~1% of all pairs; note that this includes pairs that are already connected by cross-references). Of these, most similarities are much less than one:

The largest number of neighbors in common is eight, for D&C 18:26–D&C 90:9 and Mosiah 21:15–D&C 101:7. The largest pool of unique neighbors goes to 1 Ne. 19:10–2 Ne. 25:20 with 59, although they only share two of these neighbors.

Verses with the same set of neighbors

More than 1700 of the nonzero pairs actually share all of their neighbors. For example, Deut. 5:17 and Matt. 5:21 do not reference one another, but they both have connections to Mosiah 13:21, 3 Ne. 12:21, and D&C 42:18.

The vast majority of these pairs share only a single neighbor. For instance, Deut. 8:11 and 3 Ne. 28:35 both have a single connection to Hel. 12:2. Despite having high Jaccard similarity, these verses are not obviously related, and it seems prudent to impose an additional constraint on the number of shared neighbors to avoid spurious connections. Using a minimum of two shared neighbors narrows the list to 34 suggested connections with perfect similarity.

Non-trivial cases

There are more than 3000 additional pairs with Jaccard similarity between zero and one and more than one shared neighbor. As we try to decide which of these pairs to suggest as new connections, it is helpful to compare them to pairs with existing connections:

Surprisingly, the unconnected pairs seem to have greater similarity than the connected pairs. This suggests that we should keep all the new pairs. To dig deeper, let’s consider a few examples:

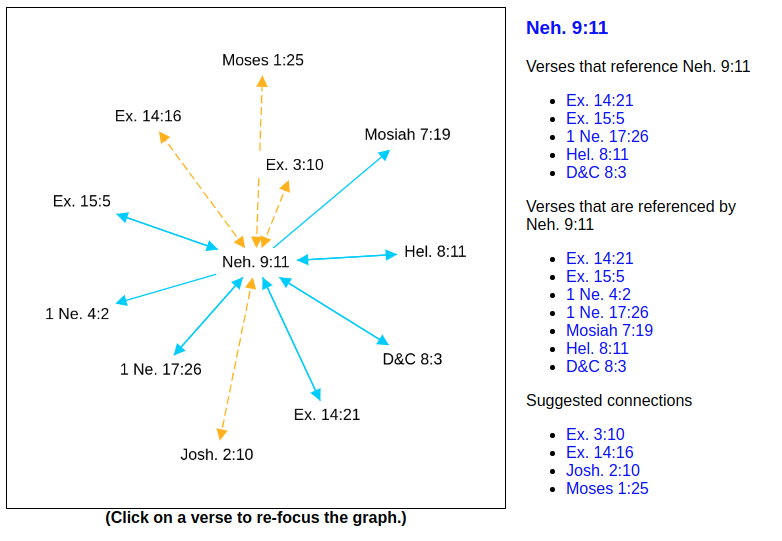

- Josh. 2:10 and Neh. 9:11 have six shared neighbors and a Jaccard similarity of 0.6.

- 1 Chr. 9:3 and 2 Chr. 15:9 have three shared neighbors and a Jaccard similarity of 0.75.

- 1 Ne. 19:10 and Mosiah 3:5 have two shared neighbors and a Jaccard similarity of 0.04.

To my eyes, the 1 Chr. 9:3–2 Chr. 15:9 pair is not especially interesting, but the other pairs are clearly good candidates for new connections. However, the verses from Chronicles do have several keywords in common, so it’s not unreasonable to suggest a connection between them.

Thus we see

This post focused on leveraging the existing connections between verses to suggest additional connections; in total, we identified more than 3000 potential connections. As with the existing cross-references in the Standard Works, not every suggested connection is going to be relevant for every use, but my hope is that some of them will be relevant for some uses!

As I mentioned in the introduction, the Connection Explorer includes the newly suggested connections:

Stay tuned for Part II of this post, where we will use machine learning to measure the textual similarity between verses and suggest new connections. Importantly, this will be our first opportunity to “rescue” some of the singleton verses that have no connections to the rest of the Standard Works.

The code used for the analysis and figures in this post is available on GitHub.

© Copyright 2020–2022 Steven Kearnes. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.